Posts from the ‘Contributors’ Category

Our favourite and inspirational teacher of editing, Alan Miller, who teaches dedicated workshops as part of our MA Visual Anthropology programme is also a director and producer. We were really proud to hear that his debut feature, Kelling Brae, won the Best No Budget Feature at the London Independent Film Festival 2012.

In his words:

It all started, as most filmmakers’ influences so often do, in the dark.

I was the textbook blank page and it took Lampwick’s transformation into a donkey (Pinocchio), mankind’s transformation into the Star Child (2001 A Space Odyssey) and my stunned disbelief (the Mothership from Close Encounters) to propel me into a career in film.

I trained as an editor at the BBC in Cardiff, South Wales and took menial jobs on any features I could land being employed on two by Rick McCallum (Star Wars fans, vent elsewhere).

After coming runner up in The Lloyds National Screenwriting Competition in the late 80s, I decamped to London and was astounded at how many producers failed to smash my door down begging me to make their sagging second act work.

Speaking of work, I suddenly realised that rumbling stomachs don’t un-rumble themselves without sustenance so I walked into the first production company I could find and started doing what I’d been trained to do. At Partridge Films I learned how to tell stories, worked on some award winning wildlife films and figured out that working with people with real fire in their bellies was something I grew to love. You don’t get rich making wildlife films.

While editing a BBC Natural World, I got a chance to direct a documentary back at the BBC based on the fans of the greatest TV show ever made™, The Prisoner (1967). Despite the lure of the animal world into which I was immersing myself, I was anxious to break out into drama.

Back at Partridge, I learned to write and was eventually entrusted with directing, writing and producing a four part series on those who work in the Serengeti National Park. I was offered the first Steve Irwin show to direct (I turned it down out of a concern about where the genre was heading – Clue? Celebrity). I started work in Holland editing features. I directed, wrote and cut numerous documentaries for a Dutch company and managed to squeeze out a few screenplays (one of which got a commendation from an American competition).

And then it hit me – just before the HD revolution, damn it. The time was right to make a feature. After an extraordinary number of technical snags, screw-ups and hard drive crashes, it seemed as if its post-production would never bear fruit. One-person film-making is tough particularly if you have to keep working (and teaching) but there were no topical considerations in my little drama about two sisters-in-law fighting over their dead husband/brother. So softly, softly…

With the help of many talented friends, it’s made it out of post-production hell and into a dazzling new spotlight of sorts. So here we are… ‘

Ever wondered what visual anthropology is all about? What does it include, and what sort of research is conducted by visual anthropologists? We thought you might, so we’ve put together a short video compiling some of the work from the MA programme at the University of Kent, UK.

The programme teaches students a range of visual techniques to allow students to explore the world of anthropology – techniques ranging from still photography, to digital video making, to social media. With a number of external experts teaching on the course (for example the photographer James Kriszyk, the editor Alan Miller, campaign filmmaker Zoe Broughton to name but three examples), as students on this course we learnt a huge amount, not just about the academic applications of visual anthropology, but also how it can feed into the wider world at large, and ultimately therefore a more publically engaged anthropology. As a result our final projects have ranged from exploring life within a community of people with and without learning disabilities in Kent, to documenting threatened traditional medical systems in Ladakh, to looking at the impacts of their work on human rights workers, and much more besides. But enough from me: watch the video and explore what visual anthropology is all about yourself.

This weekend (20 – 22 Jan) at The Bargehouse (on the South Bank in London) there is an important, exciting event that challenges comfortable narratives that our waste can be contained, cleaned and endlessly recycled through resource recovery, and reclaims waste as a filthy, powerful and potentially dangerous material flow that has to be reckoned with.

Visitors are invited to bring an unwanted item of clothing and to follow its journey as it is sold for reuse and recycling across the world. Invisible global waste economies are brought into public view, as do the people involved and the impact that these businesses have upon their lives.

The show contextualises this research with collaborative projects including Meghna Gupta’s debut film Unravel and photographs by Tim Mitchell, both focussing on the shoddy industry in Panipat, north India. Lizzie Harrison of Remade in Leeds will host workshops on upcycling old clothing and rug-making from scraps, and a piece of textile designer Kate Goldsworthy’s resurfaced shoddy textile will be on display. And Oxfam introduces its innovative ‘Frip Ethique’ social enterprise in Senegal, which sorts unsold clothing from the charity’s UK shops for sale in the local market, creating livelihoods and raising vital funds for its work in West Africa.

On Saturday 21st Jan, ‘Talking Rubbish’ sees researchers, designers, filmmakers, business entrepreneurs and third sector leaders engage with the issues raised and their implications for the way in which we think about our old clothing.

Come along with a garment to donate to our charity shop and discover the hidden journey of the clothes that you recycle.

We have a unique opportunity for home and EU students to do a fully funded MA and PhD at our school.

The deadline is looming, so if you are interested please read the further details here and submit your application.

The use of visual research methods is often celebrated as a useful method in participatory research. But what happens when the research centres on vulnerable people, including people with quite profound learning disabilities? How can you conduct participatory research in these communities? Are visual methods appropriate?

During the research for my MA dissertation I had to confront all of these issues. I spent the summer of 2011 with the community of L’Arche Kent as part of the research for my MA thesis. My research explored concepts of home and community, and how it is within these structures that the community enables an environment of acceptance and equality for people with learning disabilities that is so rarely achieved in the wider society. The final product of my research was a dissertation in two parts: the film Living Together (above) and a written thesis (read it here).

Who are L’Arche Kent?

Part of the wider L’Arche International community (5,000 people in over 130 different countries), L’Arche Kent is a community of over 100 people with and without learning disabilities living in six houses across Kent. The severity of disability in the community varies from mild with only minimal support needs to profound with intensive one-to-one, or sometimes two-to-one 24-hour support needs. The ages in the community range from 0 – 60 something, and right now there are people from 17 different countries in the community.

Evidently, if I wanted to conduct inclusive research in such a community I had to use a method which not only cut across age barriers, but which was also understandable to people from different countries as well as accessible to people of many differing abilities. Which meant I needed a very accessible research methodology, something that would enable participation by even the most disabled people. And so I decided upon video.

Why Video?

Video lent itself to this research because of its flexibility and the number of ways it encourages participation between the researcher and the people they are collaborating with. It also meant I could produce a final version of the research which was accessible to the community. Video really lets people take part in a way that more traditional research methods do not. This is especially true with people who are non-literate and / or non-verbal, or with learning disabilities of varying degrees, who may not be able to undergo long conversations or interviews.

Cameras, video and TV are a part of everyday life here in the UK, and as such are understood and understandable to the majority of people. Add to this the flexibility that filming provides and we start to see some of the advantages of using this method: I had people filming me, filming themselves, filming each other, putting on plays for the camera (alone and in groups), directing me and each other, interviewing me and each other, helping in the editing, taking part just by being in the room and occasionally shouting suggestions. People borrowed cameras to film their own lives; some people simply enjoyed watching what was going on. The beauty of a camera (both still and moving) is the number of people who want to take part. And because people were having fun it made my research really easy – I had no issues with access, no problems with getting people to take part and most importantly no issues of people feeling disconnected and therefore exploited by the research. This also meant that the community had equal ownership of the project. All of these meant that most people within the community wanted the project to succeed as much as I did, which made a huge difference, and helped balance the ethnographer – informant relationship in their favour.

Using Steady Wings to improve accessibility

One of the major factors helping make video accessible in my research was the use of Steady Wings. Designed by filmmaker Leonard Retel Helmrich, Steady Wings are an amazing piece of equipment which offer a range of filming possibilities outside of the traditional norms. You can see them in use during Sarah’s portions of Living Together – nearly all of her filming was done using this equipment. In my research they helped make a camera easy to use for less mobile people, and less intimidating for many others – having the camera mounted on a set of Steady Wings allowed people to easily hold and move with the camera, pass it amongst themselves, or simply explore different angles and views – offering different views of the world, smoother movements, and the freedom to play without worry. They took the worry out of handling unfamiliar equipment and made it fun, and ultimately led to a much greater involvement by some of the disabled members of the community than I originally imagined possible.

Of course as with any research there are some aspects of using film that need care and consideration: informed consent was a concern; ensuring people understood what was happening was sometimes challenging, although not as challenging as managing the expectations of some members of the community who thought they were going to become famous Hollywood stars following my time in the community, and the one problem that I did not forsee was the difficulty in getting back some of the borrowed cameras at the end of the research period! Whilst some have argued that any research with vulnerable people is exploitative, I personally believe that so long as proper care and consideration is taken, these issues are no more complex in conducting research with people with learning disabilities than with any other group, and in fact film offers quite the reverse, allowing people to speak for themselves, rather than have others speak for them.

I really enjoyed my time with L’Arche Kent. As well as being integral for my MA thesis, the filmed work has enabled me to produce a number of shorts which L’Arche Kent are using on their website, and I continue to be involved in the community. My findings on home and community made a contribution to the literature, but in the end the learning I will take away from this was that research in difficult circumstances becomes, if not easy, then at least possible, if you use a method that allows people to be involved as much as possible and to feel really involved. I’m not sure there is a better method than video for this, but that point remains open to debate.

Ouzoud is a village undergoing rapid change. Once a quiet Berber community in the foothills of the Atlas Mountains, the last 10 years has seen it become one of Morocco’s major tourist destinations, receiving between 70,000 and 80,000 visitors a year. The main attraction: the Cascades d’Ouzoud, a spectacular set of waterfalls in the centre of the village, mentioned in popular guidebooks and advertised in Marrakech tour company windows. Two years ago, in the sweltering heat of mid-July, I traveled three hours from Marrakech in the back of an old Mercedes taxi to visit a Dutch friend who had recently bought a guesthouse there. But, upon my arrival in Ouzoud, I was surprised by what I saw. The waterfalls were beautiful and the landscape was impressive, but what about the large pile of smoldering rubbish? What about the dirt tracks that villagers used as roads? Surely, this was not typical of a major tourist destination that seemed to promise tranquility and natural beauty. I began to wonder how I can answer these questions and how I can better understand the complex relationship between tourists and locals. So, I returned to Ouzoud this spring to conduct fieldwork and produce a short documentary film as part of my MA dissertation project in Visual Anthropology, allowing me to explore these issues in further detail.

My film, entitled Ouzoud, addresses many of these issues in the anthropology of tourism, complementing the written dissertation. But, it was also conceived as an experiment in ethnographic cinema, to find an engaging and appropriate technical, aesthetic and theoretical form that such a cinema could take. I began with the premise that all films, including documentaries, are “created, structured articulations of the filmmaker and not authentic, truthful, objective records.” Just like tourists seeking some form of visual authenticity and, at times, perhaps even believing they have found it, documentary film often pretends to show the truth when, in fact, it is portraying a heavily mediated version of reality. By making full use of thematic and dramatic editing techniques, I deliberately brought out the contradictions of tourism and the irony of many statements made by participants. I edited the film to reveal, through a variety of interviews and scenes of Ouzoud, the hosts’ and guests’ differing conceptions of tourism (at times echoing the ironic undertones Dennis O’Rourke uses in Cannibal Tours). Imagery such as a young child riding a donkey as a modern car drives next to him and Doug exiting his shiny Land Rover followed by a shot of a beggar, combined with engaging music and dynamic editing create a film that makes powerful comments on the nature of tourism. Ultimately, I share Jean Rouch’s enduring belief that ethnographic films should not be confined to the “closed information circuit” of academia, but that, ultimately, “ethnographic film will help us to ‘share’ anthropology,” through the use of such techniques. Hopefully, the film has done that.

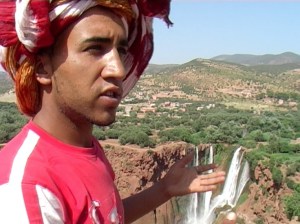

Hamid, a young tour guide from Ouzoud, describes the effects of tourism on his village, with the waterfalls behind him. “If there are big hotels in the village, and after there is another one and another one, then maybe we are going to have factories and we are going to have a lot of pollution,”Hamid ponders. “I like to see everything traditional, everything as it was in the past. I mean, we would like some development, but not something other.”

In the end, Ouzoud finds itself as a village at the frontiers of mass tourism, where a problematical course of change is currently unfolding before our eyes. Scattered with holiday homes, guesthouses and campsites, its markets sell souvenirs and postcards, while countless restaurants serve couscous and tagine to tourists. Even now, just months after leaving Morocco, I have learnt of a new, Western-style supermarket being built in the center of the village. But, most importantly, Ouzoud is just one of thousands of villages like it, undergoing similar changes all over the world. It is now up to visual anthropologists and other social scientists to document, interpret and present these changes in new and effective ways. Throughout my written dissertation, I asked how tourism in Ouzoud can be defined, how it broadly affects the village community and how hosts and guests perceive one another. Meanwhile, if tourism really does have the potential to catalyze such immense global change then, through the film, I have explored whether a more visual, even cinematic, study of tourism will help illustrate that.

Watch the film below or on Vimeo here!

You must be logged in to post a comment.