‘Then tell me who that

me is, or the

you understood, the any of us….’

(excerpt from Human Atlas by Marianne Boruch)

.

A couple of months ago I had to have an operation. On fieldwork in Cambodia at the time, I flew to Bangkok, and following a couple of uncomfortably contained weeks in hospital, I was discharged from hospital clutching a folder brimming with papers – the record of my time in hospital. A few weeks later, on a sweaty afternoon in Phnom Penh, I sat looking through the folder and came across a CD of pre-operative CT scans. As I flicked through the images, I started thinking about my perception and conception of my body and its place in my interactions in the world, something I had become acutely aware of through being sick.

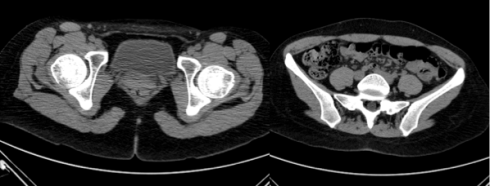

As anthropologists we are encouraged to reflect on our position within our work. But I had not really considered the place of my body within my research beyond its colour and gender. Thinking about the body is nothing new to anthropology of course; in 1935 Mauss wrote about the body as a tool for experiencing the world, and hundreds of others have examined it since, but as I considered the scans, I started to think about the place of the visual in this articulation. I spent the afternoon examining each image, fascinated by this exotic presentation of my self, at once both recognisable and completely alien. A central method in anthropology is the decentralisation of the self; that movement in perception back and forth between the known and the unknown, from that which is familiar to that which is not. Looking through the images I found myself experiencing this othering, and thus contemplating how we know our physical selves – our bodies – our ultimate research tools through which we interact, communicate and contemplate.

The physicality of the body is often de-emphasised in social anthropology in favour of approaches that examine the culturally constructed meanings inscribed on it, the symbolic aesthetics presented, or the performance of power that the body enables for example. But as I slowly recovered in the unbearable heat and humidity of Phnom Penh, the physicality of my own body was impossible to evade; it was impossible to think of the understanding of my body as simply a product of specific social, cultural and historical perspectives. Kirmayer argued that the body provides a ‘structure of thought that is, in part, extra-rational and disorderly’ due to its relation to emotional, aesthetic and moral worlds; my thought processes and engagement with the world and others within it were entirely disorderly at this time due to their connection to the physical and the altered control of agency of myself and others on my body. Examining the images, meanwhile, made me contemplate the relationship between the visual and the body: how much of our understanding of the body (our own and others) is influenced by what we see and how those images are presented, particularly in a medical setting?

These images were central to the relationships I became enmeshed in during this period. They also marked a distinct interplay of power relations. In his 1991 examination of terror in Northern Ireland, Feldman argued that power is embedded in the body and thus the body is an instrument of agency in power relations. Whilst I am not suggesting that my experiences are anything resembling those faced by people in Northern Ireland during the troubles, I certainly became aware of the power the body wielded – both to myself and to others – and it was through the imaging that power was often articulated. I lost the power of control and interpretation of my body and others gained it – only certain doctors could take the pictures, certain others could read those images, whilst still others could decide the actions taken on me. My ‘docile body’, to steal Foucault’s term, caused a period of ontological insecurity which lasted some time and it seemed, as I contemplated these images, that it was initially through the visual that I began to regain power over my body, and my feeling of self.

Cross-sectional scans of upper legs showing femoral-pelvic articulation (left) and pelvis showing iliac-sacral joints (right)

The interactions that occurred in the hospital, although in Thailand, were firmly embedded within Western medico-legal theories and histories. I wondered how a spirit-medium or soothsayer in Cambodia would interpret the pictures (particularly as I first got sick whilst visiting a mass grave), or how others would interpret them as a layperson. The images of my body were not simple transmitters of information. They were articulations of power, tools of communication, mechanisms of thought. As I travelled through my body, via the CT images, I experienced an odd disjuncture: my inners looked alien and animal-like and brought to mind the dehumanisation I had felt whilst in hospital. At the same time I felt belonging: I recognised elements of a body that exists only inside me – my peculiarly crooked spine for example, which bends at the top of my lumbar vertebrae, but which is invisible from outside to another person. I made a journey in understanding of my body from pure physicality and hyper-awareness of its workings to aesthetic appreciation and awareness of its symbolic nature.

Now several weeks on I am intrigued by the process my body has gone through, and part of my reflecting on this caused me to produce the visual journey through my body that you can see here. There is a form of Buddhist sect in Thailand that attempts to understand the cosmos by meditating over the corpse. Perhaps I am performing some such form of meditation; right now this period is central to my fieldwork experience and has informed my initial interactions with Cambodia. How does the way I use and view my body affect my communication and relationships with others and therefore my research? Have the physicalities and resultant impact on my sense of being affected my sense of self and therefore how I interact in the world? Certainly they did at the start. The images and charts provided a shared language to certain members of my social circle and were completely exclusionary to others including, at first, myself. What effect has this had on my understanding of my place in my fieldsite?

My current research looks at contemporary understandings of and relationships with mass graves in Cambodia. I feel a more embodied concept of how the body is used to influence and coerce people, how it can be a focal point of power relations, how our own understanding of ourselves is central to the understanding of the world we engage in. The bodies that fill the graves in Cambodia are perfect examples of the manipulation of power using the body. More than that, my understanding and views of the graves themselves has been altered through this visual approach to contemplation. The CT scans offer a slice of my body in time and space; they represent a small, fragmented part of a much bigger whole, which each image hints at but none shows. The graves that exist today in Cambodia are layered by years of living; each year as the rains come the layers move and elements of bodies begin to emerge before being hidden again – bone shards, small pieces of cloth – visible in part but hidden in whole and wholly incomprehensible if you do not know what lies beneath. As I think about my own journey through my body, I also start to think about relationships with the graves; this ebb and flow of visuality that at once both offers power and voice to those skeletons whilst simultaneously removing it. I don’t mean to be facile; I’m not trying to claim that my experience lends me any deep understanding of the graves, only that it has offered a new way of looking at them as they are manifested in everyday life.

I’m not sure exactly what the visuals of my own scans symbolise to me. The losing of myself perhaps – the loss of control over myself, and the uninvited and uncontrollable agency of other people within my body. The physicality of my interactions with the world. The place of my body as a tool of communication, and as an embodiment of power relations. The beautifully alien aesthetic of the body. And the way that something that I know and own so intimately is also something from which I am completely disconnected.