Posts from the ‘Contributors’ Category

The screening and exhibition of third year anthropology student visual projects took place over a long afternoon in Marlowe Lecture theatre. The event was attended by a large group of students, staff and people who had featured in the films. We were especially happy to see Caroline Grundy, a longstanding member of staff who had recently retired. For many years she had wanted to be present for the whole event.

This year’s photographic display covered a wide range of themes, demonstrating a common desire among students to engage with people in the local area and explore anthropology’s relevance for making sense of cultural difference in Southeast England.

Topics covered include the Kurdish Newroz (New Year) celebrations in Finsbury Park, sexuality, tattooing, Canterbury and its cathedral, cultural greetings, Canterbury markets and more. Photographic work by Katie Bowerman, Bianca Corriette, Helen Delmar, Myrthe Flierman, Sophie Giddings, Tabitha Hamill, Ville Laakkonen, Sarah O’Donovan, Sophie Tyler, Emma Ward and Matt Weston was exhibited in the Marlowe Foyer. Glenn Bowman judged the three photography prizes.

The theme of people’s engagement with place was also very strong in this year’s video projects. The Cathedral featured in two meditative films by Charles Beach and Claire McMurtrie.

We were extremely happy to welcome Professor Roger Just back this year. His popularity and inspiration in the year of his retirement had prompted the students that year to suggest a prize in his name. This was the last year that students taught by him were still at Kent. We were very happy to welcome a longstanding friend of the school Professor Hugh Brody, and previous Stirling Lecturer, to award a prize in his name. He took time from a intensive schedule of screenings of a groundbreaking film project that documents an indigenous land claim in South Africa.

In 2011 he gave a retrospective of his work at Kent. Our third judge, Dr Kate Moore, is also a documentary filmmaker and had recently been awarded her PhD in visual anthropology for a project in collaboration with the Powell-Cotton Museum on their Angolan collection that led to a major exhibit, ‘TALA! Visions of Angola’ that gained widespread acclaim. As the teacher of the course last year, we were especially interested to hear her opinion of the changes in filmmaking styles and focus from last year’s cohort, screened as ‘Self Spaces’ .

We reflected on the students last year and what were they doing now. Nazly Dehganiazar and Harriet Kendall won the Roger Just and Hugh Brody prizes last year for their films ‘Canterbury’s Buskers’ and ‘Voices from the Back Seat’ and we were all very moved to watch their video messages from Holland and the US. Nazly is now doing an MA in Social Anthropology, while Harriet is using her anthropological skills, in the year before going to film school, as the cultural adviser in the English Village in Disneyworld.

Films were grouped into themes related to peoples’ engagement with space and introduced by the teacher of the video project, Mike Poltorak. After the screening of a group of films, the directors came to the front for a Q and A. If you’d like to make your decision about your favourite film please feel free to view and read about them before you read the judges’ choices below.

Initiative

Noisy Neighbours Michael Selmes

Why Whitstable? Anastasia Sotiriou

Discontinuous Space Claire McMurtrie

Ethnochoreology Shaheen Kripalani

Expansion

Cathedral Triptych Charles Beach

More Human Kane Taylor

The 1882 Movement Harry Farrell

Grounding

Using the Stour Michael Bonnington

Starry Chi-An Peng

6 Miles Southeast Oliver Hall

The Lives We’ve Lost Bhokraj Gurung, Danny Mahaffey

Longevity

Anglo-Deutsch Edward Coates

Under My Skin Olivia Maguire

From East to West Carmen Yam, Thomas Slatter

The Art of Being Lost Elinor Turnbull

Hugh Brody spoke about the high quality of films this year and how so many of the films deserved a prize. He reviewed all the film drawing attention to particular things he liked in each film. The judges’ decision however was unanimous. The Hugh Brody Prize went to Charles Beach for his film ‘Cathedral Triptych’. The runner up prize was awarded to Olivia Maguire for ‘Under My Skin’.

The Roger Just Prize for Visual Anthropology went to Chi-An Peng for ‘Starry’ and the runner up prize to Harry Farrell for ‘The 1882 Movement’.

The Audience Prize was voted on by a large audience of students, visitors and staff. It went to Elinor Turnbull’s ‘The Art of Being Lost’. The runner up prize went to Carmen Yam and Thomas Slatter’s ‘From East to West’. It was a close vote with the difference between 1st and 2nd only one vote and closely followed up by Bhokraj and Danny’s film, ‘The Lives We’ve Lost’ picking up a large number of second place votes.

The prize was awarded by Alex Woodcock, representing our very active student group TRIBE, and Kate Moore. TRIBE organised the first ever undergraduate conference (Breaking Bubbles) in anthropology in the UK.

For the photography prizes there were three categories and a special mention.

Katie Bowerman won the prize for Innovative Photography.

Tabitha Hamill won the prize for Best Set of Photographs.

Ville Laakkonen won the prize for Best Anthropological Content and received a special mention. As a visiting student from Finland, Ville was particularly happy to receive this accolade and commented on how studying at Kent had been an incredible beneficial experience.

The three prize winner’s work is currently on permanent display outside the visual anthropology room in the Marlowe Building.

Students and staff joined together to thank the teachers of the visual anthropology projects course this year, Matt Hodges (Photography) and Mike Poltorak (Video), for their inspiration and considerable work that went into preparing the exhibit and screening. Mike Poltorak thanked the students for their energy and creativity and expressed the desire for them to keep in contact after graduation to help inspire future generations of visual anthropologists.

You can see photos of the event here. You can also see all the films and read more about them in the dedicated blogs above.

We’d love to read any comments in this blog or in our facebook group, UK Visual Anthropology especially related to how these films can be useful more broadly. Please post the films you like on your networks so that our students get the wider recognition they deserve.

Video Prizes Awarded

Cathedral Triptych Charles Beach (Hugh Brody Prize for Visual Anthropology)

The 1882 Movement Harry Farrell (Roger Just Runner-Up Prize)

Starry Chi-An Peng (Roger Just Prize for Visual Anthropology)

Under My Skin Olivia Maguire (Hugh Brody Runner Up Prize)

From East to West Carmen Yam, Thomas Slatter (Audience Runner Up Prize)

The Art of Being Lost Elinor Turnbull (Audience Prize)

Using art and audiovisual methods with migrants in Spain: an interview with Francesco Bondanini

February 13, 2013

Siroccosky

Francesco Bondanini, a University of Kent alumnus, uses participatory visual methods to explore and empower the lives of migrants and detainees in Spain and Germany. In the interview about his work below, he describes how the use of visual methods not only enables a greater depth of experience and knowledge, but more importantly, allows people to become involved and benefit from his work in a much more meaningful way.

Tell us about the project you are involved in right now?

I have just finished the first part of a project called “Marcaré” in Melilla. Together with a team we worked in the periphery of the city with vulnerable groups, mostly from Amazigh origin (Berbers). We used art and audiovisuals as a tool to empower people and as a means for them to recover their surroundings. It was a participatory project, in the sense that we worked together with young people and women with the aim to transform the area where they lived.

How and why did you get involved?

Knowing about my PhD, in which I used many art and audiovisual methods, Dr. José Luis Villena, a professor at the University of Granada, believed I could coordinate the project, and the Instituto de las Culturas, a public institution that works on cultural projects in the city, funded it. Together we started collaborating with local NGO Melilla Acoge with whom I had worked during my PhD, with the Red Ciudadana por la Paz, and with neighbourhood associations that made it possible for us to get into these areas.

‘Marcaré’ uses visual methods developed during your PhD: can you tell us about your PhD and how you started to use these techniques?

I studied Communication at the Lumsa University in Rome and I have always been very interested in Social Sciences; once I started my PhD I believed I could use what I learnt at University about photo and video in my anthropological research.

Throughout my PhD I broadly studied the situation of migrants dwelling in a particular place – the so-called European border zone. Specifically, my research focuses on the everyday-lives of migrants living in the CETI (Temporary Permanence Camp, as per its Spanish acronym) in the autonomous city of Melilla, a Spanish enclave in Northern Africa. Through qualitative criteria and analysis, I researched into the way a wide variety of migrants, such as Subsaharan Africans, Algerians, and Asians, rebuild their lives in this border zone. I paid particular attention to migrants’ strategies of integration and their structural and social exclusion.

In this research I used a participatory methodology that employs audiovisuals and art. I ran workshops on photo, video, radio and theatre to migrants and then debated the results with them. I also used audiovisual techniques during interviews.

What methods do you use in your current work and how have these developed from those used in your PhD?

During my fieldwork I used a sort of participatory approach with the migrants that were living in the CETI of Melilla. I ran audiovisual workshops; that was also a way to get in touch with migrants. Following these we organized exhibitions of their works, a Seminar and a theatre piece too. The visual work provided a way to create an open climate of opinion about their problems in the city, and a way to make their stories visible to the rest of the citizens. In the new project (Marcaré) I used the experience gained from the projects in my PhD and applied them within a different group and context. I worked with an amazing team, and with a higher level of organization (and a higher budget) we were able to reach more people.

What difference do you think visual methods make?

I believe the use of visuals is a way to make the work accessible to a larger audience. This kind of work sometimes risks not being so “academic” but I believe it helps to make some kind of advocacy. On the other hand, I believe in the approach that is based on the fact that the groups with whom we are working make the visual and artistic products; we often limit our role to coordination of activities only.

What happens to the work produced in this project?

I believe in the importance of showing the works, to prove what has been done and to share peoples’ stories and reach a wider audience. I spend a lot of energy preparing exhibitions within the districts of the people in order to show to the other inhabitants their work. These exhibitions are also a way to make visible ideas of transforming the surroundings. We also worked through performances, murals and artistic installations in the districts, and each of these enabled many other people to share and understand.

Any examples?

We worked a lot in a district called Monte María Cristina. We held three exhibitions of photos made by the young pupils that participated in our workshops. We usually held these in the Neighborhood associations that we had worked in for the original workshops. On one occasion some of the pictures were pasted on the walls of the district. At the opening of another, the pupils performed an “action painting” in front of an improvised audience.

We also painted two of the patios of the prison of the same barrio. The two murals were created and painted by the prisoners. This was the process: we presented our idea (to paint the patio) and told them to think about what they wanted to see in their patio, something they didn’t have or couldn’t see inside the prison. Karima Soliman, an artist who is part of the team, put together their ideas and sketches and then we moved onto the wall. We spent almost two weeks working with them on the mural, debating ideas and the painting process. This was one of the best experiences of the project; and this is how I conceive the participation approach.

Good stories? Bad stories? Things you would change?

Good stories: Fortunately many. Last week Trini Soler, a technician of the RNE (National Spanish Radio) that also collaborates in “Marcaré”, told me that she met a young pupil who had taken part in our radio workshop. The pupil discovered that Estitxu González, another member of the team, was performing a theatre piece and she decided to go. When the young pupil met Trini, she asked her when we would be going back to the Monte to follow up with the workshops, because she had lots of things prepared. We are possibly the first team that is using artistic and audiovisual tools to involve people, especially the younger people in cultural activities in these areas. The fact that the girl went to the performance of my colleague made me think that we are going in the right direction, trying to make culture delve into these barrios.

On another occasion, we painted a mural in a park in the Pinares, a zone in another marginal part of the city. When we arrived the park was in a bad condition. We followed the same process as we did in the prison; in this case working with young pupils. They created and painted the mural with the help of Manolo López, a professor at the Schools of Art in Melilla and part of our team as well. We were afraid that the mural would only last a few days before being destroyed, because as they told us, this is what normally happens. Instead, after almost six months the mural persists intact on the wall. The mural was our way to improve the park and give it back to the youth that are living there; to transform it into a space to play.

Bad stories: There are a few anecdotes related to bureaucracy and our relations with the Centre in Granada that was our partner in the project; unfortunately the relation was not so fluid.

I would like to continue with this project. We would like to transform it into a sort of Programme, i.e. something that could be permanent. The team is now working on parallel projects but we would like to start again with “Marcaré” in a few months, so yes, we would like to change into something bigger.

Have you noticed any changes in people through being involved in these visual projects?

Yes. I believe audiovisuals are a way to let people express their feelings. We gave them training and then they were able to express better their need to transform the reality where they are living or improve their quality of life. Audiovisuals and art give people the power to express themselves. We also tried to give them useful feedbacks and suggestions. Once a young student from a public school where we held a photo workshop confessed: “maybe I will not be a professional photographer, but I hope that in the future I will travel all over the world to immortalize every place and moment with my camera”.

How has your work changed through the process (academic and none)?

I started using Visual methods because I find it fascinating. Then I started to use participatory methodologies because I felt that the result of the interviews was better if I moved from behind the camera to beside the camera; making the subject feel more comfortable while he could manage the situation better. I believe that in this way I could reach different and better data, more in agreement with the kind of research I do. On the other hand, l believe in the methodology I use, because it gives me the chance to know the world I am studying from the inside; the workshops are a way to get in contact with people and establish relations that eludes from the duality of interviewer-interviewee.

When I started “Marcaré” I felt that I should be surrounded by a team of professionals of audiovisuals and art, for this reason I looked for people with this profile to join the team. As a result, the quality of the workshops and the works produced definitely improved.

What advice would you give to people trying to work in visual methods?

I would suggest they get in touch and talk with the people with whom they are filming, establishing the way to use visual methods. Sometimes these people feel uncomfortable but we don’t understand it. I also suggest trying to collaborate with the interviewee, in this way the work will surely gain something from the experience as well.

And what’s next for you?

I have just landed in Cologne (Germany). I will be here until June developing a research project funded by the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service) at the University of Cologne that involves Spanish migrants living in the city. I will use visual methods and a participatory approach in the research. And as I mentioned before, we hope to take “Marcaré” to the next level in the not too distant future.

Francesco B. Bondanini (interview by Caroline Bennett)

For more info about the project MARCARÉ, visit:

Web (in English): http://marcaremelilla.wordpress.com/in-english/

On Facebook: Marcare Melilla: arte y transformación social

On Twitter: @marcaremelilla

Last week my friend Paul Christensen invited me to attend a ceremony of spirit mediums with him. The day was fascinating – full of sounds, smells and sights and whole new part of Cambodia I had not yet experienced. I spent the day taking photos (as usual), the full gallery of which can be seen on my flickr page here. I’ve also added a few below.

People in Cambodia mostly don’t visit spirit mediums to negotiate and understand the past; they visit them to deal with the present and plan the future. Between the pair of us (Paul and I), and many other researchers besides, we were expecting spirit mediums to be one of the avenues people used to negotiate the terrible period of civil war and conflict in the 1960s and 70s, and in particular the horrific violence wrought by the Khmer Rouge from 1975 – 1979. But this appears not to be the case. That period of history is not approached through ghosts and spirits; it is experienced and integrated into today’s life in a million different ways, some of which I am exploring in my research on mass graves. But the mediums are an important part of Cambodian life for a whole host of other fascinating reasons, and if you want to know more I’d drop Paul a line!

Back in August 2012 I spent a day at the Vietnamese floating village at Kampong Chnnang, central Cambodia. Lying at the mouth of the Tonle Sap Lake, much of the town of Kampong Chnnang spends half the year beneath the water. Allowing for this, many of the local people have adapted their lives and homes, whilst the local Vietnamese community lives entirely in a floating village; living their lives on the water in floating houses, shops on boats, and livelihoods which make the most of the surrounding water and wetlands: subsistence based on fishing and wetland rice farming. I took a lot of photos that day documenting the everyday life on water of the floating village, and I was fortunate to have some of the photos I took selected to be part of the Intimate Lens Festival of Visual Ethnography in Caserta, Italy in December last year. Now you can see the full gallery on my flickr page. Here’s a taster below. Enjoy!

‘Then tell me who that

me is, or the

you understood, the any of us….’

(excerpt from Human Atlas by Marianne Boruch)

.

A couple of months ago I had to have an operation. On fieldwork in Cambodia at the time, I flew to Bangkok, and following a couple of uncomfortably contained weeks in hospital, I was discharged from hospital clutching a folder brimming with papers – the record of my time in hospital. A few weeks later, on a sweaty afternoon in Phnom Penh, I sat looking through the folder and came across a CD of pre-operative CT scans. As I flicked through the images, I started thinking about my perception and conception of my body and its place in my interactions in the world, something I had become acutely aware of through being sick.

As anthropologists we are encouraged to reflect on our position within our work. But I had not really considered the place of my body within my research beyond its colour and gender. Thinking about the body is nothing new to anthropology of course; in 1935 Mauss wrote about the body as a tool for experiencing the world, and hundreds of others have examined it since, but as I considered the scans, I started to think about the place of the visual in this articulation. I spent the afternoon examining each image, fascinated by this exotic presentation of my self, at once both recognisable and completely alien. A central method in anthropology is the decentralisation of the self; that movement in perception back and forth between the known and the unknown, from that which is familiar to that which is not. Looking through the images I found myself experiencing this othering, and thus contemplating how we know our physical selves – our bodies – our ultimate research tools through which we interact, communicate and contemplate.

The physicality of the body is often de-emphasised in social anthropology in favour of approaches that examine the culturally constructed meanings inscribed on it, the symbolic aesthetics presented, or the performance of power that the body enables for example. But as I slowly recovered in the unbearable heat and humidity of Phnom Penh, the physicality of my own body was impossible to evade; it was impossible to think of the understanding of my body as simply a product of specific social, cultural and historical perspectives. Kirmayer argued that the body provides a ‘structure of thought that is, in part, extra-rational and disorderly’ due to its relation to emotional, aesthetic and moral worlds; my thought processes and engagement with the world and others within it were entirely disorderly at this time due to their connection to the physical and the altered control of agency of myself and others on my body. Examining the images, meanwhile, made me contemplate the relationship between the visual and the body: how much of our understanding of the body (our own and others) is influenced by what we see and how those images are presented, particularly in a medical setting?

These images were central to the relationships I became enmeshed in during this period. They also marked a distinct interplay of power relations. In his 1991 examination of terror in Northern Ireland, Feldman argued that power is embedded in the body and thus the body is an instrument of agency in power relations. Whilst I am not suggesting that my experiences are anything resembling those faced by people in Northern Ireland during the troubles, I certainly became aware of the power the body wielded – both to myself and to others – and it was through the imaging that power was often articulated. I lost the power of control and interpretation of my body and others gained it – only certain doctors could take the pictures, certain others could read those images, whilst still others could decide the actions taken on me. My ‘docile body’, to steal Foucault’s term, caused a period of ontological insecurity which lasted some time and it seemed, as I contemplated these images, that it was initially through the visual that I began to regain power over my body, and my feeling of self.

Cross-sectional scans of upper legs showing femoral-pelvic articulation (left) and pelvis showing iliac-sacral joints (right)

The interactions that occurred in the hospital, although in Thailand, were firmly embedded within Western medico-legal theories and histories. I wondered how a spirit-medium or soothsayer in Cambodia would interpret the pictures (particularly as I first got sick whilst visiting a mass grave), or how others would interpret them as a layperson. The images of my body were not simple transmitters of information. They were articulations of power, tools of communication, mechanisms of thought. As I travelled through my body, via the CT images, I experienced an odd disjuncture: my inners looked alien and animal-like and brought to mind the dehumanisation I had felt whilst in hospital. At the same time I felt belonging: I recognised elements of a body that exists only inside me – my peculiarly crooked spine for example, which bends at the top of my lumbar vertebrae, but which is invisible from outside to another person. I made a journey in understanding of my body from pure physicality and hyper-awareness of its workings to aesthetic appreciation and awareness of its symbolic nature.

Now several weeks on I am intrigued by the process my body has gone through, and part of my reflecting on this caused me to produce the visual journey through my body that you can see here. There is a form of Buddhist sect in Thailand that attempts to understand the cosmos by meditating over the corpse. Perhaps I am performing some such form of meditation; right now this period is central to my fieldwork experience and has informed my initial interactions with Cambodia. How does the way I use and view my body affect my communication and relationships with others and therefore my research? Have the physicalities and resultant impact on my sense of being affected my sense of self and therefore how I interact in the world? Certainly they did at the start. The images and charts provided a shared language to certain members of my social circle and were completely exclusionary to others including, at first, myself. What effect has this had on my understanding of my place in my fieldsite?

My current research looks at contemporary understandings of and relationships with mass graves in Cambodia. I feel a more embodied concept of how the body is used to influence and coerce people, how it can be a focal point of power relations, how our own understanding of ourselves is central to the understanding of the world we engage in. The bodies that fill the graves in Cambodia are perfect examples of the manipulation of power using the body. More than that, my understanding and views of the graves themselves has been altered through this visual approach to contemplation. The CT scans offer a slice of my body in time and space; they represent a small, fragmented part of a much bigger whole, which each image hints at but none shows. The graves that exist today in Cambodia are layered by years of living; each year as the rains come the layers move and elements of bodies begin to emerge before being hidden again – bone shards, small pieces of cloth – visible in part but hidden in whole and wholly incomprehensible if you do not know what lies beneath. As I think about my own journey through my body, I also start to think about relationships with the graves; this ebb and flow of visuality that at once both offers power and voice to those skeletons whilst simultaneously removing it. I don’t mean to be facile; I’m not trying to claim that my experience lends me any deep understanding of the graves, only that it has offered a new way of looking at them as they are manifested in everyday life.

I’m not sure exactly what the visuals of my own scans symbolise to me. The losing of myself perhaps – the loss of control over myself, and the uninvited and uncontrollable agency of other people within my body. The physicality of my interactions with the world. The place of my body as a tool of communication, and as an embodiment of power relations. The beautifully alien aesthetic of the body. And the way that something that I know and own so intimately is also something from which I am completely disconnected.

Not too long ago I was fortunate enough to be invited to be a discussant at the Göttingen Ethnographic Film Festival Symposium, Participatory – what does it mean? Participatory cinema and participatory video under consideration. Participatory is a word we hear with increasing frequency in visual anthropology, particularly in relation to filmmaking (indeed I have used and written about participatory video on this blog). But the word is often bandied about with little consideration to what it actually means, either in theory or in practice.

![We Want [U] to Know presentation at GIEFF Nou Va and Ella Pugliese (film-makers) talk about the participatory process](https://ukvisualanthropology.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/img_0297.jpg?w=300&h=225)

Film-makers Nou Va and Ella Pugliese discuss their use of participatory methods in their film ‘We Want [U] to Know’

During the GIEFF symposium we spent three days talking about this term, and its practical applications. Turns out there is almost no consensus on how the term is used, with just about everyone using and understanding the term differently: from hardcore believers who advocate no input in the video / film-making process themselves, to others whose use of the term relates only to their seeking feedback from certain participants. To still others anything anthropological is participatory, because anthropological knowledge is built through intersubjective relations with others, and thereby participatory in their very nature. Neither did we come to a consensus on the term during the three days. But we did have a lot of interesting debates, some of which were fairly energetic, particularly those concerning whether the methods robust enough to be used in academic research?

Participatory video and participatory cinema essentially have two different theoretical foundations, but as time goes on and their popularity grows, the terms are becoming increasingly blurred. Evolving out of Development, Participatory Video (PV) is about working as a group to solve a problem. It assumes an issue to be dealt with, and insists on limited or no video-making from the ‘facilitators’, but on all elements of the video-making process being done by the participating community. But there are many issues caught up in these assumptions: to assume a problem in a community inevitably creates one, although it may not be the one that is the most important or pressing to various people in the group. To assume that a group or a whole community is inherently honest, cohesive and homogenous is both unrealistic and problematic. To insist that communities would be video-making if only they knew how, and we are the ones who can teach them that is both paternalistic and derogatory.

Participatory cinema meanwhile was a term initially developed by David MacDougall in opposition to Observational Cinema: participatory cinema encouraged an active participation from the film’s subjects, although mostly with the control being maintaining by the director / film-maker. It shares some intellectual concepts of Jean Rouch’s ‘shared anthropology’, not least in that in reality the levels of participation are somewhat limited and in some cases appear to be more a wave in the direction of a contemporary buzzword.

Narratives on participatory methods tend to be celebratory. Many filmmakers and researchers (myself included) have been somewhat over simplistic in their discussions on the subject, and whilst the positive aspects of the methods have been repeatedly emphasised, there is almost no critical discourse on the subject. It does exist (for example Wheeler’s (2009) article on her work in Brazil outlined several issues) but it is hard to find. One of the subjects that repeatedly arose throughout the symposium was the potential of participatory methods in anthropological research. Anthropology is about learning about other peoples’ worlds. This might be explored through participatory methods, but can we really learn the intricacies and nuances of life in a group? Anthropological knowledge is built on intimate relationships of trust, which are invariably built up one-to-one. How do you build trust and intimacy in a group? How can you avoid ‘invisible’ power relations from acting? Can you get to the discords that are so telling about informants’ lifeworlds? What about the missing voices: who doesn’t take part and why? Do participatory methods encourage a simplified version of events that ignores the complex nuances of community issues? Is a film made using participatory methods really any more ‘honest’ and ‘authentic’ than a more traditional film? What effect does the participatory method have on the actions and attitudes of the community?

The disjunctures that inevitably exist within communities, and the nuanced complexities of life are rarely (if ever) made apparent in participatory film or video, which almost exclusively present communities as cohesive, homogenous groups with shared aims and desires. As anthropologists we should be careful of presenting such simplified stories. On the other hand, good anthropology includes reflection by the researcher on their position, assumptions, presentation of the other, and effect on the research. Participatory methods potentially help this reflection, especially where participants have active control of the media: by enabling people to present themselves, participatory methods encourages the researcher to question their presentation of others, and it potentially can encourage a more collaborative, inter-subjective building of knowledge. In addition, using methods such as PV may allow us to align our research interests with the concerns of the community, which is an ideal ethical position.

To really explore the potential of PV as a research tool we need to push beyond the celebratory nature of most presentations and critically analyse both the potentialities for use, and our motivations for using it. We need to avoid the assumptions and paternalistic approach that so often accompany discussions on participatory methods: that they avoid hierarchy and power relations; that the story heard is the most important one; that everyone who wants to be involved is able to; that visual methods are the best (or automatically culturally appropriate) mode of exploration.

This post may sound extremely critical of the use of participatory methods. That’s not my aim: I think there is a strong potential in their use both as a research tool and as a means of encouraging collaboration and a more engaged, public anthropology. But before unquestioningly adopting these methods, we have a duty to ourselves, our discipline and, more importantly, to our participants to question our motivations behind their adoption, and to assess their place in our work. Only when we have asked these questions of ourselves, and addressed our concerns, should we jump in to participate.

Missed Self SPACES 2012? See the photographic exhibition of Visual Anthropology here!

July 10, 2012

Siroccosky

Don’t worry if you were not able to make the screening and exhibition of Visual Anthropology projects completed by undergraduate students from the University of Kent this year, you can see the winning films here, and the photographic exhibition has now gone virtual below. We hope you enjoy it.

(You can also see the photos in all their glory on our flickr site here)

A Visual Anthropology Screening & Exhibition

In this year’s combined screening and photography exhibition we witnessed a tremendous amount of creativity and commitment to wide anthropological engagement.

The photographic exploration of Self S P A C E S took place in the foyer of the Marlowe Building. Comprising a mixture of students’ final projects and coursework, the subjects ranged from explorations of self and other, to documenting the transformation from animal to meat in an abattoir, to photographic explorations of museum curation. A steady stream of viewers took time to admire the work (including some of our local builders, who were thoroughly impressed!) and the high quality of work was commented on by many. The judges had an incredibly hard time deciding on the prizes for each of the categories, and after an hour of deliberation, the only way they could reach a consensus was to add an extra prize. Congratulations to the following winners:

Most Innovative Use of Photography – Harriet Thomas for her project ‘Hair and Identity’

Best Anthropological Context – Freya Williams for her project on Stonewalling in North Wales

Best Overall Photograph – Special Commendation – Matt Bullard for ‘Pig in an Abattoir’

Best Overall Photograph Winner – Holly Turner for her set ‘Brutiful Derby Girls’

The video project students presented their video shorts in a full afternoon of screenings, discussions and finally the awarding of prizes. Each group of films was introduced by Kate Moore before the films were shown back to back. The directors then answered questions as a panel, picking up on themes that linked their films. The judges included Roger Just, Glenn Bowman and last year’s winner of the Roger Just Award for Visual Anthropology, Max Harrison. Hugh Brody awarded his prize for Visual Anthropology by video.

The Roger Just Prize for Visual Anthropology went to Nazly Dehganiazar for her film ‘Canterbury’s Buskers’. The Runner Up Prize was awarded to Natalie Bonet for ‘Sundays on the Southbank’.

The Hugh Brody Prize for Visual Anthropology was awarded to Harriet Kendall for ‘Voices from the Back Seat’. The runner up award went to Sarine Arslanian for ‘Connecting Strings: Armenian Spirit in London’.

Harriet Kendall’s film also won the audience prize with joint runners up awards going to Wilhelm Hodnebo’s ‘Tony’ and Gabrielle Fenton’s ‘In Dover, the Border’.

To see all the films and learn more about the context and reasons for their making please click on the links below:

Who are we?

Fish, Chips & Change — Lazlo Hewitt & Jania Kudaibergen

Connecting Strings: Armenian Spirit in London–Sarine Arslanian (Hugh Brody Prize-Runner Up)

Student Diet—Anja Hoffmann

Walk Like a Man— Francesca Wicks & Natalie Freeman

Where are we?

In Dover, The Border — Gabrielle Fenton (Audience Prize-Joint Runner Up)

Among Hectic: Buskers in Canterbury High Street— Sabrina Pascoe

Sundays on the Southbank— Natalia Garcia Bonet (Roger Just Prize-Runner Up)

Liminalities……

We Need to Talk about Abortion— Charlotte Claesson

Underwater Nation— Rachel Singer Meier

Invisible People – Berta Norman

Voices from the Back Seat – Harriet Kendall (Hugh Brody Prize & Audience Prize)

Through Our Eyes

Tony– Wilhelm Hodnebo (Audience Prize-Joint Runner Up)

Canterbury’s Buskers– Nazly Dehganiazar (Roger Just Prize)

Seeing Comes Before Words—Aimee Tollan

From Visual anthropology Classroom to Turkish TV

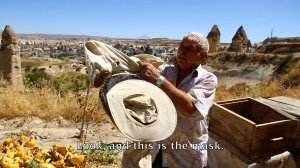

MPhil student Eda Elif Tibet’s documentary will be first broadcast on the Turkish documentary channel, İZ Tv, on the 8th June at 10.15pm. She writes about the origin of her documentary, the process of its making, and how her film was discovered on Facebook.

It was right after one of my first lessons in Visual Anthropology at Kent that I decided to realize my dream documentary project on Cappadocia. After many visits to the field site since 2007 and a long research period that took almost two years, I was just getting ready to try my first documentary. I did not have a budget, and there were no other crew members other than myself. I was excitedly getting ready to film, when my father passed away.

I abandoned everything for a while with deep sorrow and grief. But, not so long after, I realized that perhaps to continue working on this film could make me understand some of the mysteries of life and what it is to be human, in a more humorous way. My mother bought me a HDSLR, the Canon 7 D, and I bought myself a mono microphone that could be placed on the top of the camera. In the field Dr. Andus Emge and his wife Gülcan Yücedoğan Emge, who also feature in the film, were a great support. They hosted me several times in their wonderful guesthouse . I had friends all over Cappadocia, I was never alone and as I talked about my documentary idea , people seemed to be really engaged and supportive throughout the filming. The people who agreed to be filmed were more than informants to me. They were amazing characters that guided me with their light and friendship throughout the most difficult time of my life.

I shot the film in 28 days, because that was the time I had been given to complete the rest of the fieldwork and discipline myself as a first time visual anthropologist. I called Cappadocia the moon for its breathtaking moonlike landscape and also as a reference to its’ people who I thought were not quite understood; the secluded, conservative yet very friendly and hospitable cave dwellers.

I did not just want to make a film that was academically interesting but was also understandable for the people I encountered in Cappadocia. After filming enough for a rough cut I was lucky to meet with Tufan Bora, a very talented editor who has helped me a great deal. Without his assistance and great ideas on building the narrative flow for the film, I wouldn’t have achieved what I have now.

For the soundtrack of the film, I was also fortunate to be given the screening rights of wonderful songs by the inspiring musicians Alain Blessing, Ozan Musluoglu and Tunç Tandoğan. I also got the opportunity to screen the film to visual anthropologists from around the world at the Intimate lens visual ethnography film festival in Italy, to students at Massey University in New Zealand, and in a mainstream student film festival in Abu Dhabi. In January of this year I drew on the feedback I was give to edit a final version and create a short trailer. With great luck, the trailer was recognized by an editor from IZ TVon facebook. After they watched the whole film, they asked to broadcast it for a year. Iz Tv is Turkey’s first and only documentary TV channel and was founded by leading photojournalists, independent documentary film makers and media professionals of the country. In 2007 they were awarded a Hotbird TV award. Iz TV remains a highly rated national documentary channel, featuring a wide range of documentary films on issues that are vitally important for the country.

The commissioners at IZTV told me that they really appreciated the film and were curious to know more about visual anthropology (my film is the first work of its kind to be screened on Turkish TV) pointing out that they need more films on cultural heritage and tourism that communicate local perceptions. The editor who watched the whole documentary, commented: “ as a TV channel covering socio-political issues, tourism management and the protection of cultural heritage sites in Turkey are among the weakest links in the country” They also found the film cinematographically compatible and engaging as it discusses a serious topic in a humorous way . They also pointed out that for the last two years they have shot all their documentaries on HD SLRs. Having it in HD, they said, was a good asset for TV broadcast. The first of many broadcasts is on the 8th of June at 22:15pm.

Eda Elif Tibet

This post is posted on behalf of Gabrielle Fenton, a third year undergraduate at the University of Kent, and founding member of both TRIBE, and co-organiser of Breaking Bubbles, a conference supported by the RAI, the University of Kent and Radical Anthropology Group.

On the 3rd and 4th of March, I was one of many other anthropology undergrads from the University of Kent to organize a national undergraduate anthropology symposium. The theme was: Breaking Bubbles, Anthropology For Our Future. We weren’t quite sure what was going to come out of such an enterprise, but we knew that we wanted to meet other passionate students, to be confronted to other approaches to anthropology, to collectively aim at an anthropology that would be for the future. We hoped that as long as we created a good platform, interesting content would follow.

Over 100 students attended from 8 different universities, bringing with them their different anthropological backgrounds: biological, material, visual, social, etc… Over the two days, students presented projects and ideas on topics as varied as ‘human roots’ and ‘lived futures’, but through the variation, one theme was recurrent: undergrads want and need fieldwork, they want to physically engage with anthropology.

Over 100 students attended from 8 different universities, bringing with them their different anthropological backgrounds: biological, material, visual, social, etc… Over the two days, students presented projects and ideas on topics as varied as ‘human roots’ and ‘lived futures’, but through the variation, one theme was recurrent: undergrads want and need fieldwork, they want to physically engage with anthropology.

As an undergrad who sometimes feels that it is difficult to get out of a passive learning mode when sitting in a lecture room, this experience allowed me to engage in a much more dynamic form of learning. The presentations also showed how creative students are when enacting and using anthropology outside of their lecture rooms, such as a group of students from UCL who are trying to make anthropology available in primary schools. This creativity definitely enhanced my enthusiasm for the discipline, and I am pretty sure that this sentiment was shared by many others as the discussions after the talks were always very animated.

I think we succeeded in breaking bubbles, and that an anthropology for our future was a main driving force over the weekend. However, we do not see this as a finished project at all, which is why we have uploaded all the videos on this OAC page and invite every one to take part in the online discussion. You can also check out more photos from the event here. Also, the means that we used to create the platform were quite primitive and we hope to receive critiques and advice so that future events can break many more bubbles…

I think we succeeded in breaking bubbles, and that an anthropology for our future was a main driving force over the weekend. However, we do not see this as a finished project at all, which is why we have uploaded all the videos on this OAC page and invite every one to take part in the online discussion. You can also check out more photos from the event here. Also, the means that we used to create the platform were quite primitive and we hope to receive critiques and advice so that future events can break many more bubbles…

You must be logged in to post a comment.